BROADCAST SEED FIDDLES

This page lists antique hand farm tools (used mainly in England, Wales and Scotland) collected by P. C. Dorrington between 1985 and 2001.

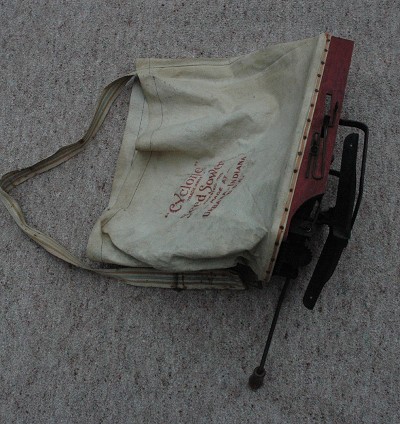

Portable, hand-operated broadcast sowing machines were introduced from America from circa 1850 onwards. The most novel, if not the most popular, of these, was the seed fiddle which took its name from the fiddle-like action required to distribute the seed. The device was suspended to one side of the operator by a shoulder strap and supported by one arm. It consisted of a canvas seed bag housed in a small rectangular box frame with a horizontally mounted finned disc which was rotated in alternating revolutions by a leather thronged bow. As the bow was moved from one side to the other with each step the sower took, a regulated amount of seed dropped from the bag onto the revolving disc which scattered it in a wide arc from 16 to 24 feet across according to the type of seed. The bag held at least 7 lbs or 3.18 kg of seed. Equal seed delivery was maintained by a jigger plate actuated by an eccentric hub on the disc’s spindle. The rate of feed, adjustable to the length of stride, was controlled by a levered slide with up to ten different settings. A metal band behind the disc prevented the seed from being thrown backward. Discs of earlier models were fitted with four fins but later versions had six. The fiddle was relatively simple to operate and sowing on both sides it was claimed that two or more acres could be sown in an hour.

Used mainly for grass and clover many of them were imported but some, notably the ‘Aero’ brand were made in Kilmarnock and distributed all over the country until recent times. In 1940 they sold for 27 shillings and sixpence plus a shilling for carriage!

Seed Fiddle, courtesy of Roy Brigden

CYCLONE SEED SOWER

Other manually-operated broadcast seeders from America appeared at roughly the same time as the Seed Fiddle. Instead of a bow, the horizontal seed distributing disc of the Cyclone Seed Sower was briskly turned by hand crank and gears spreading wheat or rye seed over an area of 30 feet or more. The seed bag rested on a simple platform which also supported the machinery. The Chicago seeder had a similar mechanism but was also supplied with a fiddle bow.

CAHOON’S BROADCAST SEEDER

Cahoon’s broadcast seed sower patented in the USA in 1861 was claimed to show from four to eight acres in an hour at normal waking pace. A side mounted hand crank with high ratio gearing rotated an open ended distributor drum mounted at the front. The drum contained four radial fins or ribs which scattered the seed in all directions as it fell from the sack through a graduated slide opening. Another form had two drums paced one above the other. The upper revolving in one direction received half the seed, the lower turning in the opposite direction received the other half of seed which possibly resulted in a more even distribution.

Although the crank operated versions produced a continuous cast compared with the fiddle type which came to a stop at the end of each bow stroke, none of these machines were completely satisfactory. The uniformity of the cast depended on the movement of the bow, the turn of the crank and the walking pace of the operator. If this were not harmonised the seed was either sown too thinly or thickly. They were best employed on small fields and in difficult areas.

A wooden green pained German model imported between the wars combined a kidney-shaped seed container with a fiddle bow mechanism that operated an under-floor rotary finned disc. It had a lid at one end, a seed inspection window at the other and was carried by a supporting shoulder strap. The seed regulator markings were in German. Measuring approx. 840 mm in length, 196 mm width and 235 mm high, they were rather bulky and heavy to carry when full with seed. Only a limited number sold.

BROADCAST APRONS – SEEDLIPS

Until the 18th century when dibbers or dibbles were first used in numbers, the common method of sowing seed in Britain was to broadcast it by hand. A sower walked behind the plough carrying the seed in an apron or a container called a Seedlip. The apron or sowing sheet was nothing more than a linen cloth wrapped around the shoulder and an arm or attached ot the waist. Seedlips generally contained between four and six gallons of seed corn (1/2 to ¾ of a bushel). They were hung on the sower’s left side by neck or should straps and supported by whichever hand was not sowing.

A sower, using his right hand, would cast the seed with each right-footed step taken to cross the field, then on reaching the end he would slide the seed lip round to the right side of his body and sow with his left hand on the way back. The casting was always made across the body in a wide fan-like action synchronized with the walking pace. Markers were sometimes placed at the headlands to ensure a straight line was taken. It was skilfully controlled work and an experienced seedsman would sow around 1 ½ acre in an hour or about 10 acres in an ordinary day. Experts could cast simultaneously to the left and right using both hands from a container strapped in front of them but the practice was not generally encouraged in England. Small seeds like ryegrass or clover had to be pinched out between thumb and finger with a twirl of the hand. Immediately after sowing the fields were harrowed to prevent birds from eating the grain. With the introduction of seed drills and other more efficient devices for sowing cereal crops the use of aprons in the south had rapidly declined by the 1850s but seed lips were still used in decreasing numbers well into this century, latterly for scattering artificial fertilizers and sowing clover or other small seed rather than corn.

The Saxons called them Saed-leaps (baskets for sowing seed) which later became seed lip or seed-lib. Other names, some provincial included seed code or cot, seed cob, an Essex basket, seedcorn or seed cup, seed mound a basket used in Suffolk, Seblet a Leics and Northants basket, seed-skip or kits, hopper, scuttle and zellup (Devon). There were several forms consequently dimensions and capacities varied. Some improvised with old home-made wooden boxes and later on with galvanized buckets held under the arms but the best shape were those contoured to the body.

BROADCAST SEED BOX

This unusual 19th century device was used for sowing clover, turnip and other small seeds. It comprised of a long narrow box fitted with a single or divided hinged lid which measured 2770 mm (9 feet) in length, 66 mm wide and 60 mm in depth. The interior was divided equally into twelve separate compartments each perforated with six equidistant holes in the bottom. These were overlaid with a piece of tin plate drilled with a corresponding number of holes of smaller diameter which allowed a single seed to pass through. To regulate the amount of seed falling from every compartment each hole could be closed off by a pivotal tin shutter shaped like a finger fixed nearby. By moving a perforated wooden slide fitted underneath the box the seed supply could be shut off. Some contained a zinc plated base with only a single aperture per compartment while other examples were fitted with copper slides along the bottom.

The box hung from a shoulder strap and was jerked from side to side with each step the sower took. Each sideways movement delivered a single seed from each opening. By varying the length of stride the amount of seed discharged in any given area could be regulated. Much however depended on the attentiveness of the operator who was also required to constantly replenish each compartment.

Improved boxes between nine and thirteen feet long were made with solid bottoms and two sliding lids which met midway. Set in the lids were a series of perforated copper slides which could be adjusted to release up to four seeds at a time from each compartment. To fill the container the lids were slid out from the centre and afterwards closed again. The box was then turned upside down and operated in the same way.

Broadcast seed boxes were already in use in the USA during the 1830’s and it is possible that some were subsequently exported to England or that a number were made here under licence. The Rev. W L Rham noted a similar device in 1844 made of a hollow cylinder and a Norfolkman Samuel Copland described a 12 foot example in 1866, but apart from one reported near Taunton by Thomas Hennell in 1934, the box appears to have been mainly confined to East Anglia where its use on certain Suffolk farms around the turn of the century was recorded. By this time however it was largely outdated.

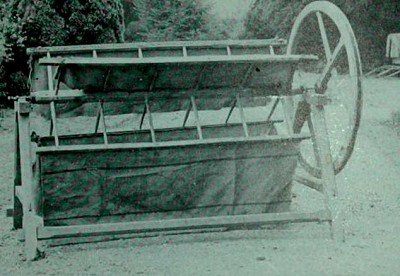

Broadcast barrow, courtesy of Roy Brigden

WINNOWING DEVICES OR SAIL FANS

Early attempts to create an artificial wind to winnow corn instead of waiting for a natural wind to blow through opened barn doors resulted in a device variously called a Winnowing, Winding or Sail Fan. The simplest and probably the oldest form comprised of three or four flaps of cloth or leather nailed directly to a hand-cranked spindle mounted horizontally on an ‘A’ shaped trestle. While one man whirled the fan around to deliver a strong and dependable stream of air, another using a wooden shovel would toss the gain into the draught to blow the chaff away. In other places the corn was shovelled into a sieve supported on a stick by a man who agitated it against the wind created. Some simply placed the unit over grain piled on the barn floor and operated it in that position. Labouring in dust-filled barns was thoroughly dirty work only sometimes relieved by using the fans in the open on suitable days.

Larger improved versions appeared, one having three or four widths of Hessian or canvas sail cloth attached to a corresponding number of supporting frames or spars which were turned by a sturdy, end-mounted, wooden-handled wheel c 1370 mm. The spindle of another less portable example jointed into a pair of heavy crossed beams about five feet (1524 mm) in length. The outer ends of each beam were capped by counter balancing blocks which provided more centrifugal force and served as a kind of governor. A polle handle with a swivel ring joined to the end of one beam was used to rotate the fan. Others were turned by an iron crank, sometimes detachable. Trestles supporting the mounted spindle stood just below waist height and measured from six or seven feet (1829-2133 mm) in length with a base width of between three to four and a half feet (914-1372 mm). Four equidistant spars up to six feet (1829 mm) long by between one and two feet (305-610 mm) wide radiated from the central shaft or spindle. The spindles themselves were approximately 1930 mm in length by 100 mm diameter and rested on two outer blocks at the top of the trestle. Cloths some eighteen to twenty-four inches (457-610 mm) wide were nailed to the outer frame ends through retaining strips of leather. Old grain sacks were often used. Construction was mainly of wood with iron collars and spindle ends. The design of the fans appears to have been fairly consistent over a long period.

In 1669 “Dictionarium Resticum” defined a ‘fann’ as “an instrument that by its motion artificially causeth winde, useful in the Winnowing of Corn”. Seven years later, Robert Plot in the “National History of Oxfordshire” related that corn could be cleaned either in a “good wind abroad, or with the Fan at home. I mean the leaved Fan; for the knee Fan (winnowing basket) and casting the corn the length of the Barn, are not in use amongst them”. Those with only a small quantity of corn could create a draught using a partially rolled sheet. “But the Wheel Fan saves a man’s labour, makes a better wind and does it with much more Expedition”.

Due to their whirling action some were provisionally called Gigs or Ginning machines, names that were also given to machinery designed to teazle cloth. Other names included Fan or Van which additionally referred to Winnowing baskets. The origin of these implements and their modest development is uncertain. Certainly they were used quite extensively in central and Southern parts of England and Wales during the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries before being gradually replaced by the internal fan bladed winnowing machine. As an agricultural implement it was not confined to Britain since other European examples existed at the same time particularly in Spain and Italy.

Only a few Sail Fans have survived two good examples being held by the Science Museum at Wroughton and the Lackham Garden Museum near Chippenham.

Winnowing Machine courtesy of Roy Bridgen

SHAULS

For smaller amounts of grain this unusual but versatile winnowing implement was used in much the same was as the winnowing basket. Known as a shaul sometimes spelt shawl, shaw or shawle, it was made out of a broad length of beechwood or sycamore oblong in shape and resembled an old butchers tray without handles. The bottom was hollowed out to a maximum depth of approx. 55-60 mm which tapered upwards to a narrowlip.

It was held in both hands and when filled the grain was tossed into an airstream to separate and remove the chaff. Shauls were also used as scoops to move grain and when turned over the perfectly straight and level rear edge served as a strike for levelling off corn filled bushel measures.

Its form is at least two hundred years old and was reported in Hampshire in 1792, in Sussex in 1904 and again in Kent. One rare example measuring approx. 710 mm in length by 297 mm width is stored by Hampshire museums. The dimensions of another from surrey are 721 mm x 270 mm.

Shawls were mainly confined to Southern England. Their shape should not be mistaken with some wooden butter making ‘bowls’ or trays which were more square and not as wide. Nor should the shaul be confused with a school, a provincial name for a wooden shovel used elsewhere to cast the corn.

CORN SCREENS

Winnowed corn still contained impurities such as weed seed, insects and dust which needed to be removed for flour making. Smaller amounts were re-cleaned by hand held sieves but greater quantities usually necessitated the use of large freestanding corn screens to sift out these impurities before it was sent to the market or the miller.

The original form of corn screen comprised of a simple oblong frame some five to six feet (1524 – 1829 mm) in length by two and half to three feet (762 – 914 mm) in width. The frame held a series of closely spaced longitudinal wires and stood at an angle of approximately forty-five degrees supported by two back legs. The grain was tossed at the upper screen with a wooden corn shovel (called in parts a scuppit). The grain rolled down the front into a winnowing basket or receptacle placed below while the smut fell through the wires to the back. Oilskin covers fixed on either side of the base were sometimes used to collect both grain and refuse.

By the 1830’s grain was fed into hoppers attached to the upper frame which regulated the amount of seed flowing down the inclined screen. Pivotal or sloping wood cross pieces called baffle plates were added to prevent corn from rebounding over the sides.

A number of similar designs were patented. One by J Francis in 1864 contained three roller brushes positioned down the frame at intervals which were rotated by hand to polish beans, oil and scourseed and to remove the ‘web from peas’ and ‘mites from turnip seed’. Another in 1875 had a number of adjustable inclined shelves or cross slates like a step ladder over which the grain jumped the open spaces while the debris fell through. By this time however Boby’s of Ipswich had already introduced their patented ‘self-cleaning and self acting corn screens’ along with other manufacturers in that period including Corbetts Hornsby & Sons, Denny & Co and W Rainforth & Sons. Most were hand operated and gradually gave way to powered machinery.

Screens were used in Tusser’s time during the 16th century. In 1825 Loudon reported that the screen was chiefly used in granaries to free corn from weevils, while in 1933 Hennell noted that millers in Kent knew it as a Scry. Those in Sussex and Surrey however called it a Scroy but elsewhere its earlier similarity to the musical instrument caused it to be known as the Corn Harp.

BARLEY HUMMELLERS

Handheld hummellers were used to remove the awns or beards from barley after it had been threshed by flail or the early threshing machines. Many were made of iron by local blacksmiths or implement makers to order resulting in variation of size and shape. Some lighter steel versions were manufactured by such companies as Ransomes of Ipswich.

The hummeller had a short ‘T’ handled wooden shaft which was mounted vertically over a rectangular, round or squared shaped frame by two or four curving supports which extended up to a central socket and shank. Each frame contained a number of end-on parallel bars (typically 5 to 7) up to 2 inches (51 mm) wide. 2-4 mm in thickness and set between 1 and 3 inches (25 mm – 76 mm) apart. Overall length ranged from approximately 9 inches (228 mm) to 16 inches (406 mm)) across. Some frames were hinged or contained pivotal blades so that they could be used from the side or on a sloping pile of barley. Round frames were uncommon. To increase the number of cutting edges others were made with both horizontal and vertical bars which formed a grid of intersecting blades.

The tool was brought down in a stamping motion upon the barley, laid thinly on a wooden floor or heaped against a wall until all the awns had been broken off. It was then collected up with a wooden shovel and tossed up into a draft of air or put through a Winnowing machine to separate the several awns from the barley. The work was very demanding.

A heavier roller type, the rotary hummeller appeared in the late 18th/early 19th century which comprised of a circular drum of varying length and diameter containing up to twenty or so horizontal blades slotted around the periphery. The drum revolved around an axle held within an iron handled frame. Relying on its weight to cut the awns it was drawn back and forth over the barley. Although more expensive it required less physical exertion and proved popular in many parts of eastern England. Longitudinal blades were added forming a latticed cutting edge in much the same way as the upright version. An identical implement was used in Wales for curd cutting.

Awns were referred to as ails, avils, avels, hails, hiles or isles, etc., which were probably derived from the French word ailes meaning wings. As a consequence hummellers acquired many other provincial names including ailers (Herts) alers (Beds) awner or awning iron, aveller or haveller (Suffolk-Norfolk) clumper, piler, topper, fothering iron (Yorks) stumping iron and colier or haearn dyludo (Wales). The word hummeller is of northern or Scottish descent. The tool’s history prior to the 18th century is obscure.

Except where the need was small, many were displaced during the late 1800’s with the arrival of reliable semi-mechanical devices and threshing machines adapted for this work. A number remained in use until the 1950’s.

P.C.Dorrington, Dec. 95 – amended Oct. 1998.

TOP pages – prestigequeen.com:

- Best Chicken Egg Incubator

- The BEST chicken WATERERs

- Rat Proof Feeder for chickens

- Best Chicken Heaters

- The BEST cheap CHICKEN COOP

- The best AUTOMATIC chicken coop DOOR

- The best NESTing BOXes for chickens

- The Best Animal Repellents for Backyard

- The Best Plucker Machine

- The Best Toys for Chickens

- The best BOOKS on raising CHICKENS

- What’s the Best CHICKEN FEED?

- How to Keep Fox Away from Chickens?

- Candler Egg Tester

Contents